Stay up to date with the latest Gevers news by signing up for our newsletter.

Non-Conventional Trademark – Part 4 – Tactile trademarks: When Touch Becomes a Brand

In an increasingly competitive commercial environment, where differentiation has become essential, it is crucial for businesses to stand out. Since the removal of the requirement for graphic representation, beyond traditional trademarks such as verbal signs or logos, unconventional marks are gaining ground. This is particularly the case with tactile marks, which, despite their growing popularity, face various challenges for acquisition of protection and recognition of rights due to their unique nature.

- Focus on the Definition of tactile trademarks and their Legal Framework

- Background and Definition

“Touch” plays a crucial role at all stages of life. It is the first sense to develop in utero and the last to remain at the end of life. It is also perceived as proof of the reality of things, unlike other senses that can sometimes deceive, such as sight.

Many times, products are intentionally designed to be handled and touched and, as such, their texture and sensations are carefully considered. The sensory characteristics of the product not only serve to convey its visual and distinctive aspect, but also, to make it a unique tool to stimulate touch. When the tactile elements of a product are designed to differentiate themselves, and if they are legally protected, they can lead to the creation of a tactile trademark that reinforces consumers’ emotional loyalty.

Martin Lindstrom, a pioneer in the field of sensory marketing and renowned for his innovative ideas on how brands can influence consumer behavior, published his findings in “BrandSense“[1]. In this effort, he analyzed the impact of brand creation that involves the five senses. He asserts that sensory aspects increase consumers’ emotional engagement. He particularly argues that tactile marks, though difficult to protect, are essential for differentiation from competitors.

The tactile trademark (or texture mark) is a sign that involves using a texture to identify a company’s products or services. This specific texture can be perceived primarily by touch (such as a rough or smooth surface) or visually (such as a particular pattern on a product). Therefore, its ability to be perceived by the sense of touch and/or sight allows the texture mark to identify and distinguish a company’s products or services from those of other companies.

b. Evolution of the Legal Framework

As we have seen in previous articles in our series on unconventional trademarks, the removal of the requirement for graphic representation allows, since the entry into force in 2017 of the Regulation on the European Union Trademark resulting from the reform of European trademark law[2], the emergence of new marks.

The reform reaffirms the principle established by long-standing jurisprudence that the representation in the registers must be “clear, precise, distinct, easily accessible, understandable, durable, and objective“[3]. Now, it does not necessarily have to be graphic anymore.

The removal of the requirement for graphic representation has officially opened the way for the registration of other types of marks, including tactile marks.

Before the reform, several tactile trademarks were rejected on the grounds that they did not satisfy the requirement for graphic representation.

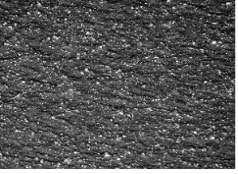

For example, the EUIPO (formerly OHIM) refused to register the mark reproduced below, claiming protection for “the soft-touch texture of the outer surface of a plastic bottle or any other plastic container” and specifying that “the mark consists of a particular surface roughness that gives a matt appearance to the surface and provides a non-sticky and soft-touch sensation when the bottle or container is held“[4] :

The Office considered that the graphic representation did not describe the requested mark with sufficient precision, and therefore, it was unable to constitute a valid trademark:

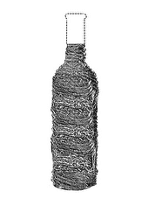

The same sanction was applied to the mark reproduced below, consisting of “the tactile sensation constituted by the embossed pattern printed on the smooth surface of the bottle“[5]:

Since the reform, tactile trademarks should no longer be rejected on this basis. However, they still need to overcome several challenges to obtain valid protection.

II. Challenges related to the protection of tactile trademarks

- The tactile trademark must meet the validity conditions set by Law and Jurisprudence

In fact, it must include the following:

- be distinctive,

- not be exclusively functional,

- be perceived as a true mark, and

- not merely as a decoration.

There have been few decisions made in this area, and one must turn to the practice of the United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) to find some examples illustrating these conditions. Indeed, the jurisprudence concerning tactile trademarks is still relatively limited, but it is evolving as more and more cases are handled by IP offices and courts.

- The requirement of distinctive character

To be protected, a tactile trademark must, like all types of trademarks, prove that it is sufficiently distinctive, either intrinsically or through its use.

The texture must be unique and not common to similar products on the market, for it to accurately identify the company behind it. It must also be able to distinguish the products or services of a company from those of other companies.

For example, the registration as a mark of the perfume bottle reproducing the shape and texture of a basketball was accepted by the USPTO, notably because of its granular texture and the offered sensation of “soft rubber touch” [6] :

More recently, the following mark described as “a cubic design formed with a brick texture on the bottom and a grass texture on the top” was registered for game software, again by the USPTO [7]:

Conversely, the registration of a tactile trademark intended to be placed on the surface of wine bottles and described in the application as a “wood bark texture” was rejected by the USPTO for lack of distinctive character. The Examiner considered that the requested mark is not intrinsically distinctive because it simply consists of “the tactile sensation of a real or simulated natural material covering the surface of a beverage bottle“. It was noted that the use of ornamental textures and natural materials to decorate beverage bottles is not rare and is probably not immediately recognized by consumers as an indicator of the origin of the products[8] :

ii. Rejection of exclusively functional trademarks

To obtain protection, the tactile quality of a product must not be essential to its use.

A famous case illustrating the rejection of protection for functional elements is the GUARANA BAWLS energy drink mark, where the raised spikes on the bottle were rejected for tactile mark protection because they had a utilitarian function (improving grip). The shape of the bottle, however, was admitted as a three-dimensional trademark by the USPTO[9] :

Another example is the rejection by the EUIPO of the trademark application reproduced below, designating manual toothbrushes and consisting of “the tactile contrast between the ribs, made of soft but rough rubber to the touch due to their arrangement, and the round pearl made of hard plastic” [10] :

The Board of Appeal considered that consumers might think that the touch and feel of holding a toothbrush handle are common variants of common toothbrush grips and/or that these features are more aesthetic or practical. For example, the rubber grip would provide a better hold for the toothbrush, without slipping, and the pearl would allow the consumer to better center their thumb and thus achieve a better grip. The Board of Appeal concluded that such a perception is likely to reduce the likelihood that these features are perceived as fulfilling the function of a mark.

In any case, granting trademark protection to a functional element would prevent other manufacturers from using similar solutions, which is against the public and competitive interest.

iii. Rejection of essentially decorative marks

Tactile decorative elements can obtain protection if they stand out and function as distinctive signs of the mark. These elements could not be registered as trademarks if they are essentially decorative.

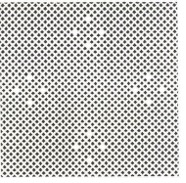

For example, KIMBERLY-CLARK, operating in the field of hygiene and health products, filed a trademark application for a raised polka dot pattern on the surface of disposable paper towel boxes, describing this pattern as a “distinctive arrangement.” However, the USPTO rejected this application, deeming the pattern to be essentially decorative and not fulfilling a distinctive trademark function[11] :

- Furthermore, tactile trademarks face difficulties in claiming recognition as they rely on touch perception by consumers, who must perceive them as a distinctive sign of the commercial origin of the products.

- In addition to consumer perception, the main difficulty for registering this particular type of trademark lies in its representation to the competent authorities. Although the former requirement for graphic representation has been abolished, the sign still needs to be capable of representation in the register in a way that allows the competent authorities and the public to determine precisely and clearly the object benefiting from protection.

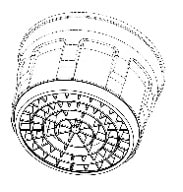

The EU court recently had the opportunity to rule on a position tactile trademark as shown below[12]:

In this case, it was an application for the registration of a trademark for jet regulators, described as a position tactile trademark, which was rejected by the examiner due to this qualification not being recognized. The Board of Appeal also rejected the registration on the grounds of lack of distinctive character. The court annulled this decision, considering that the exact reason for the refusal of the application was a lack of clarity in the representation. The tactile impression did not emerge clearly and completely from the graphic representation of the sign itself. Here, the trademark was filed before the reform, but given the arguments developed, it seems that they would have been the same today.

In practice, obtaining this type of registration appears to be challenging because the filing is conditioned upon the possibility of representing the sign clearly, precisely, accessibly, and durably; and there is currently no technique allowing reliable reproduction of a texture or tactile sensation. Unlike visual or verbal trademarks, a texture or sensation cannot, for example, be easily captured by standard visual means, and very detailed descriptions or relief images complicate this registration process.

However, this possibility is not definitively excluded, since the representation of the sign can be made “in any appropriate form using commonly available technology“[13]. With the rise of new technologies, it may therefore be conceivable in the future to see this type of trademark registered. For example, it could be relevant to use 3D scanning, modeling techniques, or tactile sensation simulators to capture the texture of the surface in high resolution and allow examiners to exactly feel the tactile sensation.

Thus, it is likely that new marketing strategies will emerge focusing on the tactile sensations of product surfaces. In the United States, some companies are already exploring this path, particularly by emphasizing the tactile sensation of furniture surfaces. Similarly, this type of development could manifest itself in the cosmetics industry, for example, by highlighting the texture of a bottle.

Beyond the challenges related to registration, issues of counterfeiting and the risk of confusion between tactile signs in practice will also need to be addressed. Consumers are not yet accustomed to using their sense of touch to identify the origin of a product or service. However, the possibility offered by trademark law could stimulate marketing developments focused on this tactile perception, which could refine our understanding of the distinctiveness and representation of this type of trademark.

In conclusion, although tactile trademarks offer a unique potential to enrich consumers’ sensory experience and strengthen brand loyalty, their recognition and protection remain areas to be explored. Technological advances, promoting the emergence of new tactile representation methods, and the development of case law will determine to what extent these trademarks can become a powerful and distinctive marketing tool. In the meantime, companies must navigate carefully in this emerging field, taking into account legal requirements and consumer perceptions and the assistance of our experts can be useful in this context.

[1] “Brand Sense: How to Build Powerful Brands Through Touch, Taste, Smell, Sight and Sound”, Martin Lindstrom – Strategic Direction, ISSN: 0258-0543, 1 February 2006

[2] Regulation (EU) 2017/1001 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 14 June 2017 on the European Union Trademark, entered into force on 1 October 2017, transposing Directive (EU) 2015/2436 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 16 December 2015.

[3] CJEU – Case C-273/00, Sieckmann v. Deutsches Patent- und Markenamt of 12 December 2002

[4] OHIM – Case 009410622 – Rejection decision of 22 March 2011 regarding the application for registration of EU trademark No. 009410622, filed on 29 September 2010 in classes 17 and 20 in the name of LA SEDA DE BARCELONA S.A. (ES).

[5] OHIM, Board of Appeal – Case R 2588/2014 – Decision of 27 May 2015 confirming the rejection of the application for registration of EU trademark No. 009410622, filed on 4 September 2013 in class 3 in the name of THE PROCTER & GAMBLE COMPANY (USA).

[6] U.S. Trademark No. 3348363, filed on May 2, 2006, and registered on December 4, 2007, in class 3 in the name of SO FRENCH PERFUME LLC (USA).

[7] U.S. Trademark No. 6857445, filed on August 30, 2021, and registered on September 27, 2022, in class 9 in the name of Tellurion Mobile (UA).

[8] U.S. Trademark Application No. 86616663, filed on May 1, 2015, in class 33 in the name of FCP “ASCONI” SRL (MD).

[9] U.S. Trademark No. 3250178, filed on November 8, 2005, and registered on June 12, 2007, in class 32 in the name of BAWLS ACQUISITION LLC (USA).

[10] OHIM – Board of Appeal, Case R 479/2012-5 – Decision of March 12, 2013, confirming the rejection of EU Trademark Application No. 009705451, filed on February 2, 2011, in class 21 under the name of THE PROCTER & GAMBLE COMPANY (USA).

[11] Trademark application number 86766780, filed on September 24, 2015, in class 25, in the name of KIMBERLY-CLARK WORLDWIDE, INC. (USA).

[12] General Court of the European Union, December 7, 2022, Case T-487/21, Neoperl AG v. EUIPO

[13] Aforementioned case, CJEU – C-273/00, Sieckmann v. Deutsches Patent- und Markenamt, December 12, 2002