Stay up to date with the latest Gevers news by signing up for our newsletter.

EPO has released the highly anticipated decision in referrals G1/22 and G2/22. What was the referral about, what did the Board decide, and what are the practical implications – read on to find out.

Case background

The two Board of Appeal decisions underlying the referral both relate to the same patent family, albeit T1513/17 is against a decision of the opposition division to revoke a European patent, whilst T2719/19 is against a decision to refuse the divisional patent application by the examining division.

In this patent family, a first US provisional application was filed in the name of three inventors, as per the requirement before America Invents Act of 2011 took effect. Subsequently, a PCT application, claiming priority from the US provisional application, was filed indicating the same persons as both inventors and applicants for only the US designation, whilst two (new) entities were named as applicants for all other designations, including EP (see Fig 1). Thereafter, upon entry of the PCT in EP, the situation was such that the EP counterpart claimed priority from a US provisional application, which did not name the same applicants as the EP, which was contentious in view of the EPC.

Figure 1.

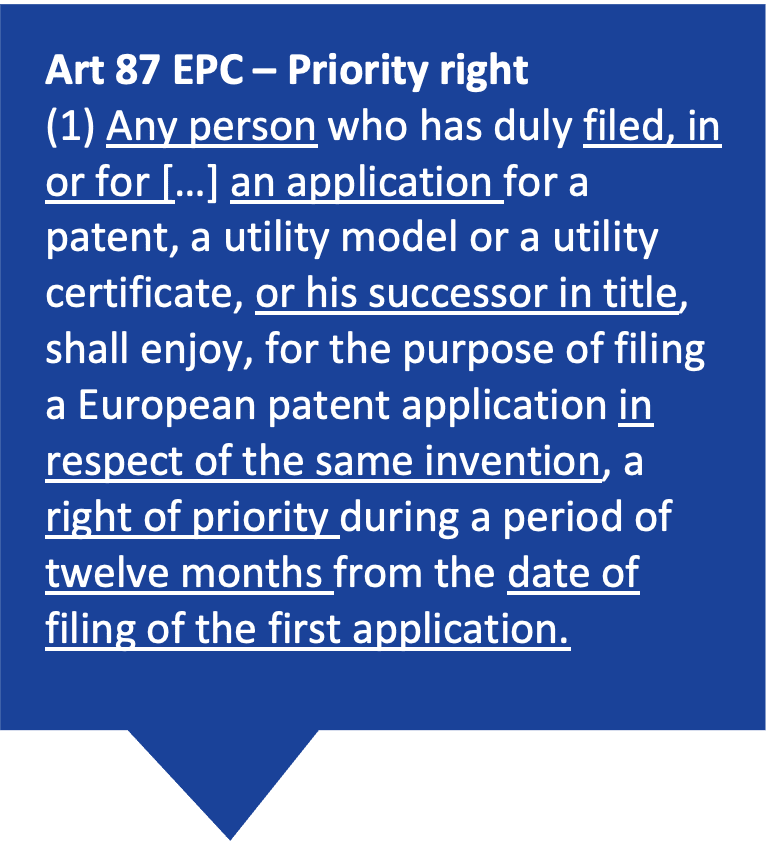

Article 87 EPC together with the Guidelines for Examination (G-F VI-1.3) dictate that, in order to validly claim priority, the applicant of the subsequent application must be an applicant or successor-in-title of the applicant of first application (i.e. US provisional in this case). Therefore, it appeared that the listed applicants would only be entitled to claiming priority if they were successors in title of the inventor(s) of the first application. The opposition filed against EP1755674 relied on this discrepancy, and questioned the validity of priority claim as it was considered to be consequential for introducing novelty-destroying intermediate prior art.

During opposition proceedings, it came to light that only one of the three inventors of the US provisional application had effectively transferred the priority right to one of the applicants (i.e. Rother to Alexion pharmaceuticals); University of Western Ontario appeared to not be a successor-in-title of any of the inventors of the first application. Apparently, even though the PCT application still listed all three inventors as applicants, albeit only for the US designation, the opposition division did not consider it to be consequential for validity of priority right.

During opposition (& subsequent appeal proceedings), the Proprietor attempted a request of correction of applicants, under Rule 139 EPC. However, the Board of Appeal cited G1/12 to state that a correction under Rule 139 “must introduce what was originally intended” and “party’s actual intention must be considered”. Based on the declaration submitted by the Proprietor (cited document D54), it appeared that the in-house counsel relied on the assumption that the other two inventors were obliged to assign their rights to the University of Western Ontario by virtue of their employment by University. The Board of Appeal opined that the in-house counsel in the declaration is “not referring to an error of expression in form PCT/RO/101 but rather to the underlying motives for this expression. However, these motives are not relevant for the application of Rule 139 EPC”.

Consequently, the request for correction was not allowed, and the patent was revoked in opposition due to the presence of novelty destroying intermediate prior art. Similar proceedings also took place in reference to the divisional application at the Examining division, with the same outcome.

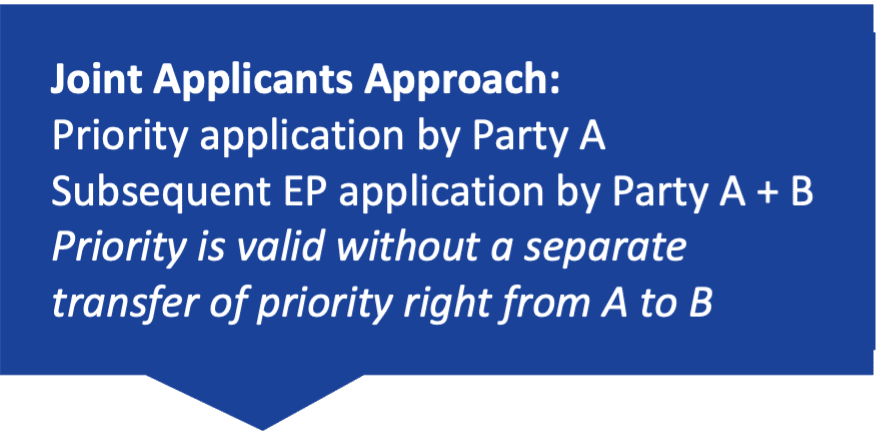

During the appeal proceedings, which were consolidated to deal with both cases in parallel, the Applicant/Proprietor introduced a new line of argument – that even if the correction under Rule 139 EPC was not allowed, the claimed priority was still valid. For this latter argument, the Applicant/Proprietor seemed to be relying on the application of the EPC’s joint applicant’s approach to PCT, whilst citing Art. 118 EPC, Art. 153(2) EPC, and Art. 11(3) PCT as support. However, the Board noted that “… present situation, where not all of the applicants for the PCT application are applicants for a European patent, is materially different from that of a regular European application. Assuming that Article 118 EPC provides a legal basis for the joint applicants approach, then its effects are limited to the applicants of a European patent..” Therefore, the Board of Appeal did not consider the application of Art. 118 EPC of relevance to the present situation.

Referral to the Enlarged Board of Appeal

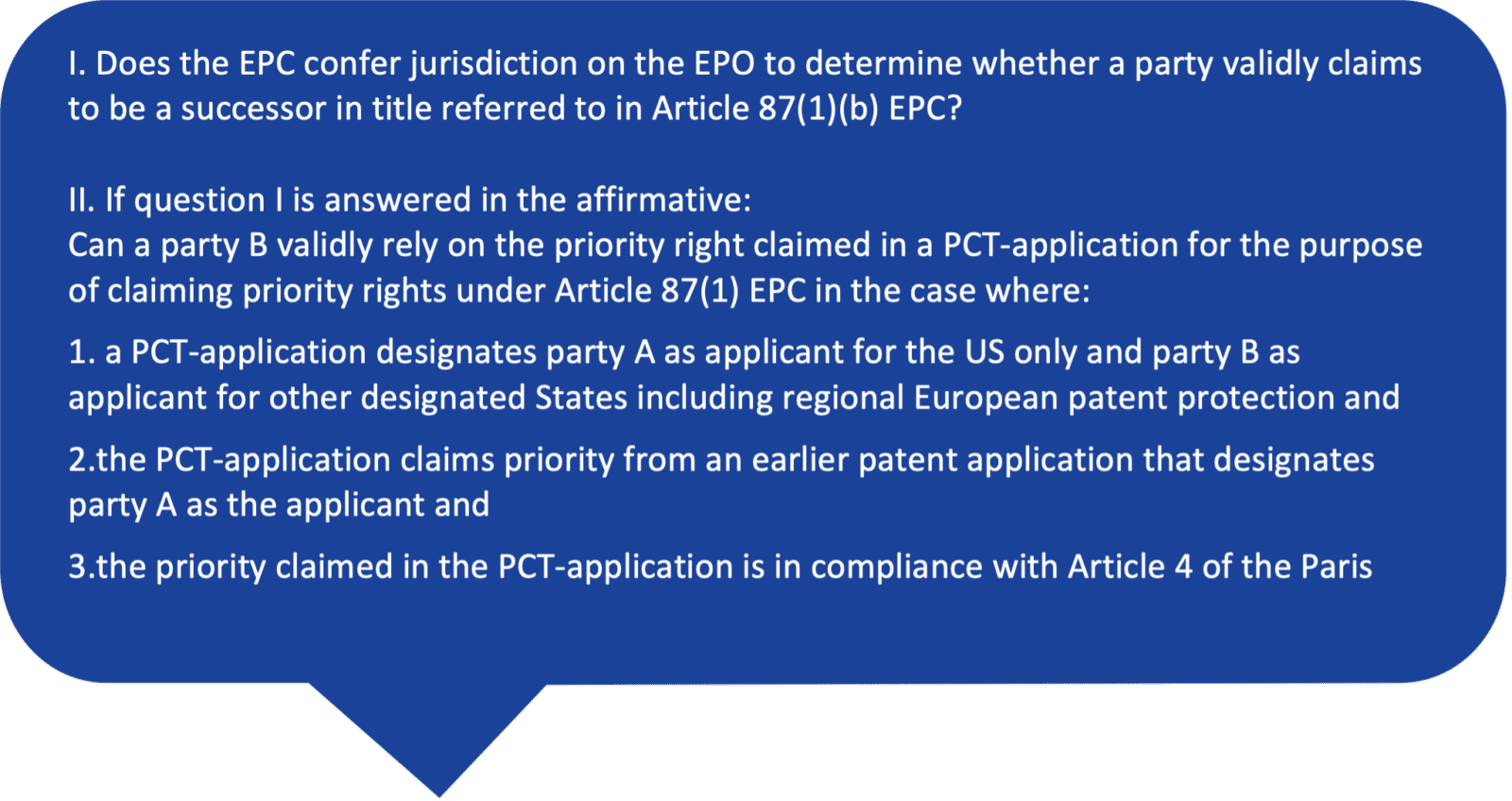

Board of appeal referred two questions surrounding the entitlement to priority to the Enlarged Board of Appeal, in order to seek guidance and clarity on the matter:

The first question seeks to determine the jurisdiction of the EPO to assess entitlement to priority, whilst the second relates directly to the validity of the priority claimed in the underlying EP case.

G 1/22 & G 2/22 – the decision

The consolidated decision in G1/22 & G2/22 answering the referred questions was published on 10.10.2023 and provides key insights on how priority rights are to be assessed at the EPO.

EPO’s jurisdiction to assess entitlement to priority

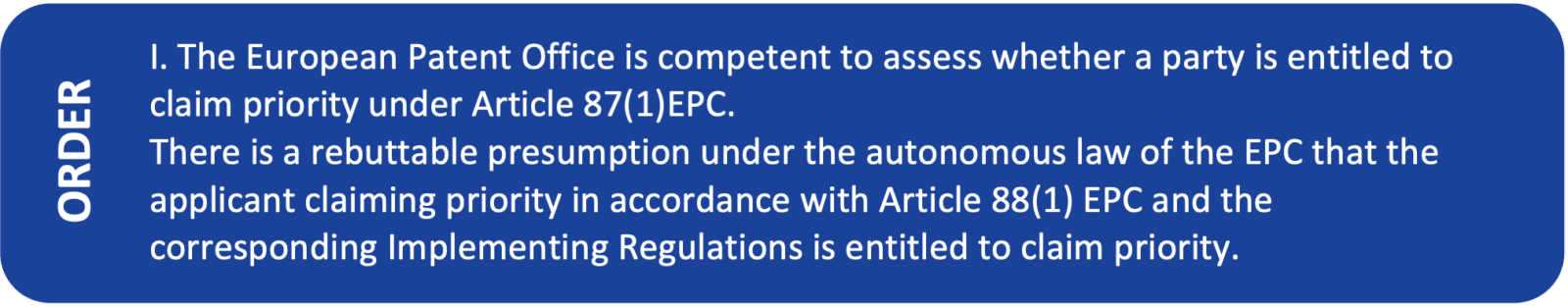

With regards to the first question, the Board seems to draw a clear distinction between the assessment of valid transfer of priority and assessment of valid entitlement to patent right. The latter is clearly under the jurisdiction of national courts, as governed by the Protocol on Recognition.

However, for assessing entitlement to priority, the Board seems to be of the opinion that applicability of national laws is questionable. The Board relies on the fact that

“Since the creation, the existence and the effects of the priority right are governed only by the EPC (and by the Paris Convention through its relationship with the EPC), priority rights are autonomous rights under the EPC and should be assessed only in the context of the EPC, regardless of any national laws”.

The Board further indicates that the assessment of entitlement of priority is consequential for determining the relevant prior art, and is ergo inextricably linked with the assessment of all aspects of patentability. On the contrary, the national courts can still assess the entitlement to patent application or patent, without having to concern themselves with issues relating to patentability of underlying inventions. Based on this line of argumentation, the Board considers the EPO to have jurisdiction for autonomous assessment of the entitlement of priority.

The Board seems to be further of the view that the formal requirements for transfer of priority rights under the autonomous law of the EPC should not be higher than those established generally in national laws. On the contrary, the Board advocates for lowest standards, and calls for even accepting “informal or tacit transfer of priority rights under almost any circumstances”. Additionally, the Board seems to doubt the relevance of requiring that a transfer of right of priority be concluded before the filing of subsequent European patent application, since priority entitlement is presumed to exist on the date it is claimed anyway.

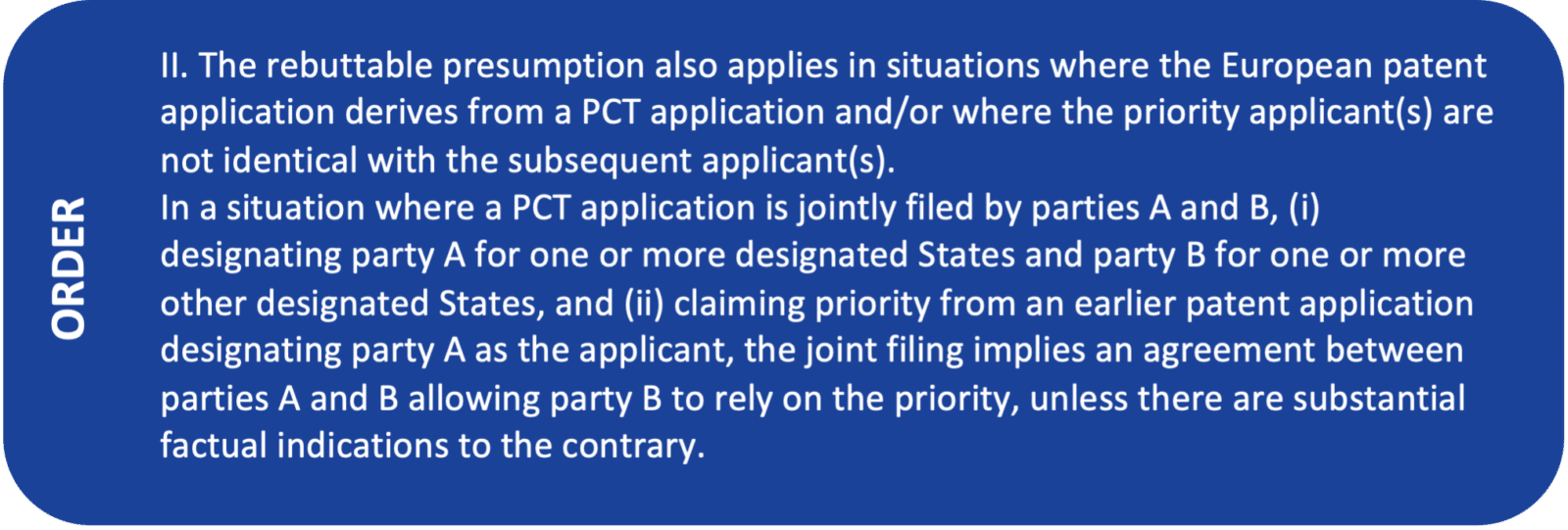

Interestingly, the Board goes on to further posit that there exists a “rebuttable presumption” under the autonomous law of the EPC that the applicant claiming priority, so long as such a claim meets the requirements of the EPC, is entitled to claim priority. In other words, an entitlement to priority is presumed to be valid, unless it is proven otherwise. With this position, the Board has essentially shifted the burden of proof in matters relating to entitlement to priority to the person challenging the validity of said claim. In the words of the Board, “party challenging the entitlement to priority can thus not just raise speculative doubts but must demonstrate that specific facts support serious doubts about the subsequent applicant’s entitlement to priority”.

Validity of priority claim <-> PCT joint applicants approach

Since the Board considers EPO to have jurisdiction over assessment of entitlement to priority, it next tackled the second question, relating to the so-called PCT joint applicants approach. The Board seems to consider that a general decision on the viability of such a “PCT joint applicants approach” is not needed, since a similar result can be achieved through a different route – namely, by applying the criteria of implied agreement.

In order to evaluate the conditions and applicability of such an implied agreement, the Board appears to (again) take a somewhat lenient approach. It seems that the Board considers even “an informal or implicit agreement” to be sufficient for transferring priority rights. The Board goes further to point out that actions such as mutual or joint filing can be considered to signal an implied agreement, insofar as there are no “clear indications to the contrary”. In other words, it appears that, in order to rebut any doubts regarding validity of a priority claim, the applicant would not be restricted to only explicit proof.

Another interesting point arising from this decision is the application of these measures in cases with a plurality of applicants. The Board seems to make a distinction with regards to consequences for rebuttable presumption and implied agreement in such cases. Notably, a co-applicant for priority application who is not involved in subsequent application may be deemed to not have consented to a transfer of priority, therefore one would be unable to directly imply an agreement. However, the Board appears to indicate that the rebuttable presumption of entitlement may still hold in such a scenario since such presumption is not dependent on whether the involved applicants acted as co-applicants at any stage. In other words, such a priority claim from the outset would be presumed to be valid. However, if it is challenged, based on “specific facts supporting serious doubts”, an implied agreement cannot be invoked by the applicant(s).

Moving forward – forecasting changes in practice

The position of the Enlarged Board of Appeal seems to indicate a divergence from the practice at the EPO so far. The rebuttable presumption is in contrast with historical practice, wherein the party making the priority claim was frequently tasked with providing proof of transfer or validity of priority claim, even in the absence of any substantiated doubts. This divergence in practice, combined with the low bar for accepting a transfer of priority right, will likely change the conduct of opposition proceedings at the EPO, which have increasingly relied on invalidating priority rights to be able to introduce intermediate prior art. It appears the Board was cognizant of such effects, as it also stated that “The rebuttable presumption concerning priority entitlement however substantially limits the possibility of third parties, including opponents, to successfully challenge priority entitlement.” Furthermore, when a priority claim is nonetheless challenged, it appears that the bar for admissible proof is fairly low, admitting even a tacit or implied agreement. The application of the decision in regards to situations with overlapping co-applicants seems to leave more room for discussion and interpretation. Could it be that the reliance on rebuttable presumption can provide a workaround to the ‘All Applicants” approach? After all, the presumption can only be challenged based on “specific facts supporting serious doubts”, which sets the bar quite high. If that’s to be the case, it can be expected to have far-reaching effects.

As always, Gevers is eager to assist you in any patent matter. Do not hesitate to contact us!